'Middle Ages in space' doesn't do justice to Warhammer 40000, which draws on elements across the tapestry of western history to create a dystopian but many-layered future universe. Where Warhammer was confined by its late medieval setting, 40K gets to indulge a smorgasboard of historical flavours - Imperial Rome, Victorian England, 20th century fascism - while keeping Elves, Orcs and other medieval fantasy staples, only adding spaceships and guns. Hardcore science-fiction buffs may sniff at such quarrying of the past as intellectually lazy and tacky, but it’s their loss.

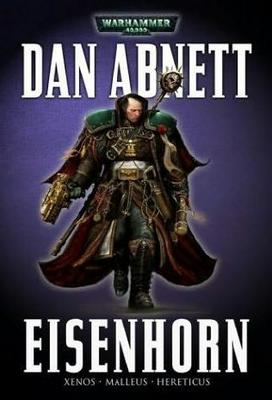

It’s their descriptive opulence in exploring this dark future that makes the Eisenhorn novels worth the read. In contrast to his Gaunt’s Ghosts series, which can qualify at a pinch as military fiction, Dan Abnett's trilogy of the plucky Inquisitor can’t aspire to the detective genre. He gives us a sequence of events rather than well-defined plot lines leading to a resolution, admittedly a criticism that could be applied to many Sherlock Holmes stories. The trick is that the reader doesn’t notice because he (more occasionally, she) is absorbed with the events themselves and the backdrop against which they take place. As Abnett acknowledges in the preface to the one volume edition, the idea was to give readers an insight into the texture of the 40K universe, so often sublimated into the pervasive violence associated with Games Workshop. The ‘storyline’ is Eisenhorn’s self-narrated personal journey, which is used to showcase the 40K universe and serve as a metaphor for its moral paradoxes, with liberal doses of bloodshed, psychokinesis and daemonancy thrown in along the way.

An Inquisitor was the obvious choice for this role, not just because he gets to travel but because the Inquisition is the Imperial institution par excellence, its raison d’etre being to root out difference within Imperial society and burn it – sometimes literally – in the name of species survival. The first paradox is obvious: to save humanity one has to crush it, in spirit and often in flesh. The second is more subtle: to fight the darkness one must flirt with it, a dilemma Abnett works out primarily through the daemon Cherubael, who despite being more a device than a character and warp spawn to boot is one of the Black Library’s more memorable creations. The implications of this ethical impasse aren’t pretty. Everything Eisenhorn is attached to as a human being (even his own body) is progressively destroyed, leaving him stalking the shadows alone, or more precisely with an imprisoned daemon for company. The God-Emperor’s work is a hard calling.

No comments:

Post a Comment