This piece is the first instalment in an Asia-Pacific politics column I'm doing for Farrago, the Melbourne Uni student mag. It overlaps with my AAP article on the

changing Asia-Pacific order, but focuses on the background politics to the new East Asian Summit and its implications for Australia.

__________________________________________________

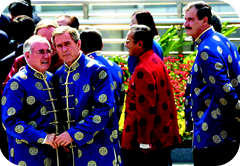

The political landscape of the Asia-Pacific is changing. The US-centric alliance system that has dominated the region since the early 1950’s is under pressure from several directions: the rise of China, the growth of East Asian regionalism, changes in US foreign policy priorities. The East Asia Summit that convenes in Kuala Lumpur this December is the most significant expression to date of these converging trends.

For over a decade China has been engaged in intense diplomatic efforts to improve its position in East Asia. These bore fruit from the late 1990’s with APEC’s displacement as the most important regional forum by the ‘ASEAN Plus Three’ grouping, which includes China but excludes the US. It is from this grouping that the East Asia Summit has emerged, representing a shift in the region’s political centre of gravity away from Washington. While the EAS will initially focus on economic issues, its architects intend it to evolve into a vehicle for regional governance and security dialogue. Combined with the proliferation of regional free trade zones, this has led to much speculation about an emerging ‘East Asian community’ comparable to the European Union, or even of a Sinocentric hierarchy resembling imperial China’s tributary system.

These prophecies are premature at best. Asia is far more diverse – politically, culturally, geographically – than Europe, and lacks the shared historical experience that underpins the EU. Regional states remain too apprehensive about China to accept a system dominated by Beijing; Japan, Singapore and Indonesia for example lobbied heavily for the inclusion of Australia and India in the EAS to balance China. Despite its diplomatic setbacks, the US remains entrenched in the region through its military presence and security ties with allied states, which have been renewed and expanded in parallel with the growth of Chinese power. The Bush administration’s readiness to court India to the point of antagonising Pakistan, a key US ally in the War on Terror, demonstrates the US commitment to curbing Chinese dominance in the Asia-Pacific.

Nevertheless the fact that an East Asian grouping (which the US has always opposed) has emerged at all shows how far American influence in the Asia-Pacific has slipped. As regional states have developed and their interactions have grown more complex, the post-1945 system of bilateral security and economic relationships centered on the US has become an anachronism. Washington’s failure to show leadership during the Asian Financial Crisis crystallised the movement for an alternative political framework to address the region’s needs, a trend accelerated by the regional stresses created by US foreign policy since 9-11. Condoleeza Rice’s absence at the recent ASEAN conferences in Laos, which finalised the basic structure of the EAS, was the coup-de-grace to US prospects for staying in the political driving seat. Increasingly Washington will have to deal with East Asia as a ‘region’, rather than simply a location for various US security interests.

These developments have produced a win-win situation for Australia. Previously confined to the fringes of East Asian regionalism as an ASEAN dialogue partner, Australia is now a founding member of the institution that will lay the basis for East Asian cooperation in the 21st century. Instead of estranging us from the US, invitation to the EAS has raised Canberra’s stock in Washington, which having itself been excluded from this emerging political architecture needs loyal allies on the inside. It seems to be the death knell for the argument that Australia must choose between Asia and the West (i.e. the United States). In reality this was always a false contention; the Labor governments of the early 1990’s promoted APEC as a vehicle to keep the US involved in the region while accommodating East Asian aspirations, particularly those of China. Hawke and Keating are often accused of courting Asia at the expense of our US relationship, but in effect they sought to have our cake and eat it too. Ironically it is the Howard government – which has emphasised Australia’s separateness from Asia, faithfully followed US foreign policy and persisted with a doctrine of regional military preemption – that has got a slice.

No comments:

Post a Comment