The Andrew Fraser saga sputters on, with enough energy to generate a bit of heat but not a really big bang. Having dented Macquarie’s reputation, the good professor’s quest to rouse the racial consciousness of Anglo-Australia recently added Deakin University to its casualty list. Faced with a prospective racial vilification suit, Deakin’s Vice-Chancellor ordered the university’s law review to axe a peer-reviewed article by Fraser, whose field is constitutional law. In the age of the internet however, someone – not necessarily in the same country – will always get their hands on the forbidden fruit. Fraser’s article is available here in full, courtesy of National Vanguard (“Standing Up for White Americans”). Nevertheless free speech isn’t worth anything without clarity, so in the interests of clearing the media smoke that’s surrounded this affair I’ve read the piece through and dissected Fraser’s argument.

His main points seem to be –

- Racial difference is a biological reality with scientific backing. Culture not simply a social construct but has a substantial biological component: it is a racial ‘phenotype’, produced by interaction between a racial group’s genotype and its environment. Cultural difference, therefore, is racially determinate and cannot simply be dissolved through common value systems or ideological creeds.

- The Anglo-Saxon phenotype is characterised by individualism, nuclear families and deemphasis on extended kinship relations. The net consequence is a relative lack of ethnocentrism among Anglo-Saxons, to be contrasted with the clannishness and xenophobia of other races (e.g. the Chinese). Thus “[Australia’s] creedal commitment to racial egalitarianism [is in reality] a defining characteristic of a distinctive European racial identity”.

- The Anglo-Saxon democracies, including Australia, are an expression of this “primordial English ethnicity” rather than of ideological creeds. Australia is founded not on Enlightenment principles of liberty and equality, but on the “non-kinship based forms of reciprocity” associated with the Anglo-Saxon race. To quote further:

“The only racial groups able to fit seamlessly into the society of strangers constituting a civic nation are those whose members can easily shed the deeply-ingrained ethnocentrism and xenophobia characterising most non-European peoples … Civic nationalism [is] a meme replicated best and most easily through the vehicle provided by the Anglo-Saxon genotype.”

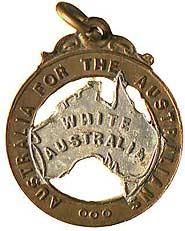

- The White Australia Policy recognised the racial basis of Australian nationhood and as such was fundamentally sound. It was dismantled by an “alliance of … pressure groups working through the corporate sector and within the centralised apparatus of state power … to flood the Anglo-Australian homeland with a polyglot mass of Third World immigrants.” These “managerial elites” seek to replace the “shared civic culture … of Anglo-American constitutionalism” with a ‘neo-feudal system of group representation’ (i.e. multiculturalism), the better to serve their own interests.

It is precisely white Australia’s lack of ethnic consciousness, argues Fraser, that exposes it to this threat:

“Faced with competition from a growing East Asian population, white Australians will find themselves outgunned: Western-style ‘old boy’ preference networks are only weakly ethnic in character, and, thus, permeable, making them no match for the institutionally-directed, in-group solidarity or ‘ethnic nepotism’ practised by other groups … within two to three decades … Australia will have a heavily Asian managerial-professional, ruling class that will not hesitate to promote the interests of co-ethnics at the expense of white Australians.”

Where conventional attacks on multiculturalism target the Left, Fraser trains his fire on “neoconservatives” like Keith Windschuttle, who advance the “pernicious tenet … that all people are equal in principle and in potential.” Fraser claims that the contemporary Right has lost touch with the “pre-political communities” in which the Australian and American nation-states are grounded; it has become nothing more than a vehicle for the interests of the “managerial elite,” interests which mandate the destruction of the “white, Christian, masculine and bourgeois values and institutions that remain the principal constraints on managerial reach and power”. The only way to avert national suicide is a political revolution:

“None of the major parties, indeed, not one member of the Commonwealth Parliament, offers citizens the option of voting to defend and nurture Australia's Anglo-European identity. The problem, in short, is clear: The Australian nation is bereft of a responsible ruling class. The solution is … the restoration of a ruling class rooted in the reinvigorated folkways of an authentically Anglo-American civic patriotism, a ruling class re-attached to the history and destiny of its own people.”

That ruling class is to be drawn from the growing ranks of “racial realists”, among whom Fraser modestly numbers himself.

There’s something perversely Marxist about Fraser’s rant, with his talk of awakening ethnic consciousness, racial base determining cultural superstructure and political revolution led by an intellectual vanguard. And as with orthodox Marxism, the argument’s sweeping reductionism is its undoing. We can start with Fraser’s reduction of western civilisation to “an evolutionary adaptation to the rigours of life in cold, ecologically adverse climates.” As far as he’s concerned, Greece and Rome don’t exist; Protestantism and the Enlightenment are expressions of biological preferences for individuality. Having excluded any possibility of non-biological cultural formation, Fraser declines to explain how cold climates select for “non-kinship based forms of reciprocity”. In fact his whole thesis is an unsubstantiated chain of cause and effect – individualistic social structures begat the common law of contract, which begat Anglo-American capitalism, which begat constitutional government, etcetera. As if we weren’t mystified enough, Fraser leaves all his key terms undefined, resulting in a conceptual fuzziness that makes his argument difficult to follow.

Unsurprisingly, such an anorexic theory doesn’t hold up well under the weight of conclusions Fraser hangs on it. He struggles to accommodate the waves of migration that produced the modern English – all individualistic Germanic peoples, he assures us – and makes his life easier by omitting other cultures that lived in cold, adverse climates but didn’t develop constitutional government (think the Russians, or Koreans). By Fraser’s logic the Inuit should be the most constitutional people in the world. As for the problem of transmuting ‘English’ into ‘British’ – the stock that gave rise to the American and Australian nation-states – Fraser postulates that minimal genetic distance between the English, Scots and Irish allowed them “to overcome their group differences when they encountered each other … merging into a new ethny possessed of its own distinctive language, religion and way of life”. He obviously hasn’t visited Belfast any time lately, or met anyone of Irish descent for that matter.

Fraser does an even skimpier job on the traits of non-Europeans, notwithstanding that these are the raison d’etre for his racial call to arms. Let’s take as an example the Chinese, who by virtue of being the greatest threat to White Australia receive the most space (two half-paragraphs). Fraser’s knowledge of Chinese ‘clannishness’ is a century out of date, the clan system having broken down among both overseas and mainland Chinese under the 20th century’s sociopolitical pressures. Regarding the “deeply-ingrained ethnocentrism and xenophobia” among the Chinese, Fraser’s claims stem from the mundane sin of insufficiently wide reading. Between the 7th and 14th centuries AD China was the world’s most religiously tolerant and cosmopolitan society, with large and prosperous non-Chinese communities in all its major cities. Events from the 9th century onwards, culminating in the trauma of Mongol conquest and misrule, introduced xenophobic elements and produced the closed society that post-medieval westerners would encounter. Nor has China’s 19th and 20th experience encouraged tolerant attitudes towards foreigners.

That still begs the question of whether Chinese ethnocentrism is in fact manifest in contemporary Australia. Fraser seems to confuse the tendency to mix with those who are like you with ‘ethnocentrism’, a deliberate attitude of not associating with people outside your ethnic group. I’ve seen little evidence of the latter in Melbourne’s Chinese community, partly explained by its internal diversity, something Fraser either doesn’t know of or conveniently ignores. As a rule, Malaysian or Singaporean Chinese are more likely to associate with white Australians than with mainlanders, for example. If there’s a defining mark of cultural heritage among overseas Chinese it’s their lack of interest in it, with most unable to tell you how many days there are in Chinese New Year, let alone quote the Confucian classics or tap other sources of their ‘primordial ethnicity’. As for institutionally-directed promotion of the interests of co-ethnics – by which Fraser presumably refers to the kongsi system – he’s unlikely to find any evidence of it in 21st century Australia, because it’s not needed in this sociopolitical environment. If anything, the Chinese are predisposed to ethnic cannibalism rather than ethnic nepotism – a ‘rope of sand,’ Sun Yat-Sen regretfully labeled the Chinese solidarity that Fraser so fears.

His main points seem to be –

- Racial difference is a biological reality with scientific backing. Culture not simply a social construct but has a substantial biological component: it is a racial ‘phenotype’, produced by interaction between a racial group’s genotype and its environment. Cultural difference, therefore, is racially determinate and cannot simply be dissolved through common value systems or ideological creeds.

- The Anglo-Saxon phenotype is characterised by individualism, nuclear families and deemphasis on extended kinship relations. The net consequence is a relative lack of ethnocentrism among Anglo-Saxons, to be contrasted with the clannishness and xenophobia of other races (e.g. the Chinese). Thus “[Australia’s] creedal commitment to racial egalitarianism [is in reality] a defining characteristic of a distinctive European racial identity”.

- The Anglo-Saxon democracies, including Australia, are an expression of this “primordial English ethnicity” rather than of ideological creeds. Australia is founded not on Enlightenment principles of liberty and equality, but on the “non-kinship based forms of reciprocity” associated with the Anglo-Saxon race. To quote further:

“The only racial groups able to fit seamlessly into the society of strangers constituting a civic nation are those whose members can easily shed the deeply-ingrained ethnocentrism and xenophobia characterising most non-European peoples … Civic nationalism [is] a meme replicated best and most easily through the vehicle provided by the Anglo-Saxon genotype.”

- The White Australia Policy recognised the racial basis of Australian nationhood and as such was fundamentally sound. It was dismantled by an “alliance of … pressure groups working through the corporate sector and within the centralised apparatus of state power … to flood the Anglo-Australian homeland with a polyglot mass of Third World immigrants.” These “managerial elites” seek to replace the “shared civic culture … of Anglo-American constitutionalism” with a ‘neo-feudal system of group representation’ (i.e. multiculturalism), the better to serve their own interests.

It is precisely white Australia’s lack of ethnic consciousness, argues Fraser, that exposes it to this threat:

“Faced with competition from a growing East Asian population, white Australians will find themselves outgunned: Western-style ‘old boy’ preference networks are only weakly ethnic in character, and, thus, permeable, making them no match for the institutionally-directed, in-group solidarity or ‘ethnic nepotism’ practised by other groups … within two to three decades … Australia will have a heavily Asian managerial-professional, ruling class that will not hesitate to promote the interests of co-ethnics at the expense of white Australians.”

Where conventional attacks on multiculturalism target the Left, Fraser trains his fire on “neoconservatives” like Keith Windschuttle, who advance the “pernicious tenet … that all people are equal in principle and in potential.” Fraser claims that the contemporary Right has lost touch with the “pre-political communities” in which the Australian and American nation-states are grounded; it has become nothing more than a vehicle for the interests of the “managerial elite,” interests which mandate the destruction of the “white, Christian, masculine and bourgeois values and institutions that remain the principal constraints on managerial reach and power”. The only way to avert national suicide is a political revolution:

“None of the major parties, indeed, not one member of the Commonwealth Parliament, offers citizens the option of voting to defend and nurture Australia's Anglo-European identity. The problem, in short, is clear: The Australian nation is bereft of a responsible ruling class. The solution is … the restoration of a ruling class rooted in the reinvigorated folkways of an authentically Anglo-American civic patriotism, a ruling class re-attached to the history and destiny of its own people.”

That ruling class is to be drawn from the growing ranks of “racial realists”, among whom Fraser modestly numbers himself.

There’s something perversely Marxist about Fraser’s rant, with his talk of awakening ethnic consciousness, racial base determining cultural superstructure and political revolution led by an intellectual vanguard. And as with orthodox Marxism, the argument’s sweeping reductionism is its undoing. We can start with Fraser’s reduction of western civilisation to “an evolutionary adaptation to the rigours of life in cold, ecologically adverse climates.” As far as he’s concerned, Greece and Rome don’t exist; Protestantism and the Enlightenment are expressions of biological preferences for individuality. Having excluded any possibility of non-biological cultural formation, Fraser declines to explain how cold climates select for “non-kinship based forms of reciprocity”. In fact his whole thesis is an unsubstantiated chain of cause and effect – individualistic social structures begat the common law of contract, which begat Anglo-American capitalism, which begat constitutional government, etcetera. As if we weren’t mystified enough, Fraser leaves all his key terms undefined, resulting in a conceptual fuzziness that makes his argument difficult to follow.

Unsurprisingly, such an anorexic theory doesn’t hold up well under the weight of conclusions Fraser hangs on it. He struggles to accommodate the waves of migration that produced the modern English – all individualistic Germanic peoples, he assures us – and makes his life easier by omitting other cultures that lived in cold, adverse climates but didn’t develop constitutional government (think the Russians, or Koreans). By Fraser’s logic the Inuit should be the most constitutional people in the world. As for the problem of transmuting ‘English’ into ‘British’ – the stock that gave rise to the American and Australian nation-states – Fraser postulates that minimal genetic distance between the English, Scots and Irish allowed them “to overcome their group differences when they encountered each other … merging into a new ethny possessed of its own distinctive language, religion and way of life”. He obviously hasn’t visited Belfast any time lately, or met anyone of Irish descent for that matter.

Fraser does an even skimpier job on the traits of non-Europeans, notwithstanding that these are the raison d’etre for his racial call to arms. Let’s take as an example the Chinese, who by virtue of being the greatest threat to White Australia receive the most space (two half-paragraphs). Fraser’s knowledge of Chinese ‘clannishness’ is a century out of date, the clan system having broken down among both overseas and mainland Chinese under the 20th century’s sociopolitical pressures. Regarding the “deeply-ingrained ethnocentrism and xenophobia” among the Chinese, Fraser’s claims stem from the mundane sin of insufficiently wide reading. Between the 7th and 14th centuries AD China was the world’s most religiously tolerant and cosmopolitan society, with large and prosperous non-Chinese communities in all its major cities. Events from the 9th century onwards, culminating in the trauma of Mongol conquest and misrule, introduced xenophobic elements and produced the closed society that post-medieval westerners would encounter. Nor has China’s 19th and 20th experience encouraged tolerant attitudes towards foreigners.

That still begs the question of whether Chinese ethnocentrism is in fact manifest in contemporary Australia. Fraser seems to confuse the tendency to mix with those who are like you with ‘ethnocentrism’, a deliberate attitude of not associating with people outside your ethnic group. I’ve seen little evidence of the latter in Melbourne’s Chinese community, partly explained by its internal diversity, something Fraser either doesn’t know of or conveniently ignores. As a rule, Malaysian or Singaporean Chinese are more likely to associate with white Australians than with mainlanders, for example. If there’s a defining mark of cultural heritage among overseas Chinese it’s their lack of interest in it, with most unable to tell you how many days there are in Chinese New Year, let alone quote the Confucian classics or tap other sources of their ‘primordial ethnicity’. As for institutionally-directed promotion of the interests of co-ethnics – by which Fraser presumably refers to the kongsi system – he’s unlikely to find any evidence of it in 21st century Australia, because it’s not needed in this sociopolitical environment. If anything, the Chinese are predisposed to ethnic cannibalism rather than ethnic nepotism – a ‘rope of sand,’ Sun Yat-Sen regretfully labeled the Chinese solidarity that Fraser so fears.

It need hardly be said that Fraser’s exoneration of Europeans of xenophobia is just as threadbare, resting on the sole basis of comparative casualty lists for the Japanese-led Broome pearl riots and anti-Chinese goldfield brawls. This isn’t the place to go into the chequered record of western humanism; let’s just note that the word ‘jingoism’ was coined with reference to the British. Chinese civilisation has its flaws, but it didn’t produce the gladiatorial arena, holy war, the inquisition, witch-burnings, colonialism, plantation slavery, racial poll taxes, the Ku Klux Klan or fascism. Those distinctions go to western civilisation, with Islam co-owning the second item.

So poor is the quality of Fraser’s own argument that we can hardly expect him to canvass counterarguments, for example that ethnic difference is entrenched sociopolitically rather than racially or culturally. Or that culture, far from being biologically imbedded, changes rapidly under different conditions, evidence for which is readily found – for instance in the foregoing discussion about the Chinese experience. Not that it matters from Fraser’s viewpoint. It’s clear from his paean to white, masculine, bourgeois values that Fraser is relying not on the strength of his academic method, but on the very sort of primordial instincts that he claims are absent in mainstream Australia. It’s a phenomenon I call ‘log-cabin patriotism’ – faced with the challenges of globalisation, people respond by seeking a return to the ‘authentic’ Australia (America, Canada, New Zealand), i.e. the Australia of the past, with its simplicity, moral certainties and above all its monocultural security. Buttressing this is the related phenomenon of tension between two emerging Australias – the cosmopolitan coastal metropolises tied to the outside world, and a monocultural hinterland haemorrhaging people and services. We see it in the current spats over Telstra and VSU (which the Nationals are stymying for the sake of regional varsity sport). It was arguably the motive force behind One Nation, which Fraser certainly situates within his argument:

“Among the managerial and professional classes, a complacently ‘cosmopolitan’ consensus reigned supreme; the political equilibrium was not upset until the meteoric rise of the One Nation party in the late 1990s. Then, for a brief, shining moment, the patriotic instincts of the more ‘parochial,’ outer suburban, white Australians found a political voice. However, much to the relief of the political class, that too often tongue-tied voice of populist protest was largely ineffectual and, in any case, was soon silenced.”

Fraser is hardly the only academic arguing that immigration poses a fundamental identity crisis for the Anglo-American democracies – Samuel Huntington and Victor Davis Hanson having recently published books on the subject – or the only voice raised against the greed of corporate and political elites. What distinguishes him is his subscription to a creed of white racehood and its apocalyptic struggle with the ‘Other’, something quite distinct from scientific inquiry into biological difference between ethnic groups, or from contemporary social issues raised by immigration. As I argued in my previous post, Fraser is propagating not rational argument but white supremacist ideology. The site on which I found his article attacks the Bush and Howard governments for their ‘Jewish’ foreign policy and celebrates 14th century Russian (i.e. White) victories over the Mongols. According to Fraser, “like any other ethno-nation, white Australians constitute a large, partly inbred, extended family” that has an “objective genetic interest” in keeping its genepool undiluted. By ‘objective’ he means that whiteness is a good in itself, independent of social, economic and political questions – a mystical quality, the sort that underpins Nazi ‘blood and soil’ cults. Fraser has given us the antipodean equivalent of the bumper-sticker slogans familiar to the US South – ‘the only reason you are white today is because your ancestors practiced segregation yesterday’, etcetera. At the risk of being sensationalist myself, I’ll quote The Amtrak Wars, which may be science-fiction but is also a political satire that captures this worldview so concisely, it’s scary:

‘The First Family is a collection of families, united by one dream … the restoration of America. Our America – good, honest and true – swept clean of striped lump-heads and yellow trash.’

In short, what we have here is far-right ideology, branded with Fraser’s academic credentials and given an intellectual gloss by phrases like ‘extended phenotype’ or ‘Anglo-American capitalism’. It’s small wonder that Fraser seems to lack any original ideas. Every second sentence of his article is footnoted; it reads as an exercise in synthesising other people’s conclusions. This is the stuff of a third-grade undergraduate essay, not a refereed academic journal. Forget vilification suits, the DLR could have cut Fraser’s piece on quality-control grounds. It belongs in the newsletter of the Aryan Front or (minus racism) the Citizens Electoral Council, not a law review.

This still leaves the question of whether Fraser’s drivel should be published at all. In fact it already has, substantial extracts from the article having appeared in last week’s Australian, which has a considerably larger readership than the Deakin Law Review. Despite the article’s explicit political agenda and defamation of a large part of Australia’s population, it should nevertheless be put to public scrutiny, in the interests not only of free speech but of denying ammunition to those who propagate these views. That would avoid the sort of negative fallout from the ‘Catch the Fire’ affair, although I’d say in that case seminars teaching about a Muslim conspiracy to take over Australia were rightly banned. Fraser’s article comes pretty close to this line, and there’d be a good case against it under the legislation that caught Catch the Fire Ministries, but in the context I doubt it could mobilise sufficient hatred against non-Europeans to justify letting it fester. A broadsheet paper is probably the best place to air it – it doesn’t grace the piece with academic respectability and it’s the most conducive forum for wide circulation and debate.

It’s sad that a man with Fraser’s education should end up knowing so little about the world. I’d go on about the difference between wisdom and book learning, but I think that I’ve rambled enough. As an upcoming member of the managerial elite, I’d better get out and start promoting the interests of my co-ethnics.

So poor is the quality of Fraser’s own argument that we can hardly expect him to canvass counterarguments, for example that ethnic difference is entrenched sociopolitically rather than racially or culturally. Or that culture, far from being biologically imbedded, changes rapidly under different conditions, evidence for which is readily found – for instance in the foregoing discussion about the Chinese experience. Not that it matters from Fraser’s viewpoint. It’s clear from his paean to white, masculine, bourgeois values that Fraser is relying not on the strength of his academic method, but on the very sort of primordial instincts that he claims are absent in mainstream Australia. It’s a phenomenon I call ‘log-cabin patriotism’ – faced with the challenges of globalisation, people respond by seeking a return to the ‘authentic’ Australia (America, Canada, New Zealand), i.e. the Australia of the past, with its simplicity, moral certainties and above all its monocultural security. Buttressing this is the related phenomenon of tension between two emerging Australias – the cosmopolitan coastal metropolises tied to the outside world, and a monocultural hinterland haemorrhaging people and services. We see it in the current spats over Telstra and VSU (which the Nationals are stymying for the sake of regional varsity sport). It was arguably the motive force behind One Nation, which Fraser certainly situates within his argument:

“Among the managerial and professional classes, a complacently ‘cosmopolitan’ consensus reigned supreme; the political equilibrium was not upset until the meteoric rise of the One Nation party in the late 1990s. Then, for a brief, shining moment, the patriotic instincts of the more ‘parochial,’ outer suburban, white Australians found a political voice. However, much to the relief of the political class, that too often tongue-tied voice of populist protest was largely ineffectual and, in any case, was soon silenced.”

Fraser is hardly the only academic arguing that immigration poses a fundamental identity crisis for the Anglo-American democracies – Samuel Huntington and Victor Davis Hanson having recently published books on the subject – or the only voice raised against the greed of corporate and political elites. What distinguishes him is his subscription to a creed of white racehood and its apocalyptic struggle with the ‘Other’, something quite distinct from scientific inquiry into biological difference between ethnic groups, or from contemporary social issues raised by immigration. As I argued in my previous post, Fraser is propagating not rational argument but white supremacist ideology. The site on which I found his article attacks the Bush and Howard governments for their ‘Jewish’ foreign policy and celebrates 14th century Russian (i.e. White) victories over the Mongols. According to Fraser, “like any other ethno-nation, white Australians constitute a large, partly inbred, extended family” that has an “objective genetic interest” in keeping its genepool undiluted. By ‘objective’ he means that whiteness is a good in itself, independent of social, economic and political questions – a mystical quality, the sort that underpins Nazi ‘blood and soil’ cults. Fraser has given us the antipodean equivalent of the bumper-sticker slogans familiar to the US South – ‘the only reason you are white today is because your ancestors practiced segregation yesterday’, etcetera. At the risk of being sensationalist myself, I’ll quote The Amtrak Wars, which may be science-fiction but is also a political satire that captures this worldview so concisely, it’s scary:

‘The First Family is a collection of families, united by one dream … the restoration of America. Our America – good, honest and true – swept clean of striped lump-heads and yellow trash.’

In short, what we have here is far-right ideology, branded with Fraser’s academic credentials and given an intellectual gloss by phrases like ‘extended phenotype’ or ‘Anglo-American capitalism’. It’s small wonder that Fraser seems to lack any original ideas. Every second sentence of his article is footnoted; it reads as an exercise in synthesising other people’s conclusions. This is the stuff of a third-grade undergraduate essay, not a refereed academic journal. Forget vilification suits, the DLR could have cut Fraser’s piece on quality-control grounds. It belongs in the newsletter of the Aryan Front or (minus racism) the Citizens Electoral Council, not a law review.

This still leaves the question of whether Fraser’s drivel should be published at all. In fact it already has, substantial extracts from the article having appeared in last week’s Australian, which has a considerably larger readership than the Deakin Law Review. Despite the article’s explicit political agenda and defamation of a large part of Australia’s population, it should nevertheless be put to public scrutiny, in the interests not only of free speech but of denying ammunition to those who propagate these views. That would avoid the sort of negative fallout from the ‘Catch the Fire’ affair, although I’d say in that case seminars teaching about a Muslim conspiracy to take over Australia were rightly banned. Fraser’s article comes pretty close to this line, and there’d be a good case against it under the legislation that caught Catch the Fire Ministries, but in the context I doubt it could mobilise sufficient hatred against non-Europeans to justify letting it fester. A broadsheet paper is probably the best place to air it – it doesn’t grace the piece with academic respectability and it’s the most conducive forum for wide circulation and debate.

It’s sad that a man with Fraser’s education should end up knowing so little about the world. I’d go on about the difference between wisdom and book learning, but I think that I’ve rambled enough. As an upcoming member of the managerial elite, I’d better get out and start promoting the interests of my co-ethnics.

2 comments:

my speculation that Fraser is a suppressed Marxist is vindicated by - of all people - Keith Windschuttle

Excellent post John. Your point about Fraser ignoring the cultural drift between overseas and mainland Chinese just goes to illustrate the fact that noone has thought of culture as a biological "phenotype" since the 1950s.

And talking about "log-cabin patriotism", those images on the National Vanguard site illustrate that perfectly.

Post a Comment