Like the Chen Yonglin scandal, April's row over MIT's online publishing of century-old woodblock prints was a localised affair. But they make for an illuminating comparison.

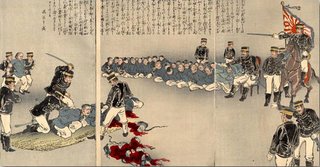

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has taken down a history course Web page after a 19th century wood-print image of Japanese soldiers beheading Chinese prisoners sparked complaints from Chinese students and led to an apology from one of the course's professors. The "Visualizing Cultures" course, which uses images from the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, was spotlighted Sunday on MIT's home page. It was pulled late Tuesday afternoon, and the school hosted a forum Wednesday for students, particularly those in MIT's Chinese community, to voice concerns. (AP)

John Dower took full responsibility for selecting the images and writing the commentary, explaining that to present propaganda images for educational use was not to condone their message... But the students could not grasp this point. Blinded by passion, they shouted that Dower and Miyagawa had been insensitive to the tremendous suffering of the Chinese people at the hands of Japanese militarism. One student undertook to edify Prof. Dower on the finer points of Japanese history by proudly presenting him with a copy of a popular book on the Nanjing massacre! Written demands circulated at the meeting included shutting down the site permanently, demands that MIT officially apologize to the offended “Chinese community,” and cancellation of academic workshops related to the site. (Perdue)

By this point an online hate campaign was under way against the two history professors involved, one of whom had the misfortune to be of Japanese ancestry. The MIT establishment was mystified as to where this outrage was coming from; it's not like images of graphic violence are hard to find on the internet, even those involving Japanese soldiers beheading Chinese victims. One group at the heart of the controversy sought to elaborate -

The MIT Chinese Student and Scholar Association, in a letter to MIT President Susan Hockfield, called for "proper historical context" at the top of the page, and asked for a posted warning that the images are graphic and racist.

"We do understand the historical significance of these wood prints, and respect the authors' academic freedom to pursue this study," the letter stated. "However, we are appalled at the lack of accessible explanations and the proper historical context that ought to accompany these images." (AP)

So what was the 'historical context' provided on the original webpage?

Dower’s text describes one such print, entitled “Illustration of the Decapitation of Violent Chinese Soldiers,” which depicted Japanese soldiers executing helpless Chinese prisoners of war, as “an unusually frightful scene.” ... He continues, “Even today, over a century later, this contempt remains shocking. Simply as racial stereotyping alone, it was as disdainful of the Chinese as anything that can be found in anti-“Oriental” racism in the United States and Europe at the time – as if the process of “Westernization” had entailed, for Japanese, adopting the white man’s imagery while excluding themselves from it. This poisonous seed, already planted in violence in 1894-95, would burst into full atrocious flower four decades later, when the emperor’s soldiers and sailors once again launched war against China.” (Perdue)

Most would read this as a mundane condemnation of Japanese imperialism, as well as context-setting for subsequent East Asian history. But evidently a great number of Chinese people read it as a national insult and dismissal of China's historical grievances. Perhaps it was the use of the adjective 'violent' for the hapless Chinese soldiers, thoughthe description might be justified given that Chinese soldiers did commit atrocities in the 1894-5 war. But had that word been absent, chances are the reaction would have been the same - on trend.

Expressing political positions through violence (verbal or otherwise) is hardly unique to Chinese people; a good many freedom-loving, rule-of-law-respecting Americans have sent death threats to everyone from the Dixie Chicks to justices of the Supreme Court. But given the series of riots touched off over the past eight years by the Belgrade embassy bombing, soccer defeats by Japan and the Japanese government's approval of questionable history textbooks, a foreign observer might feel justified in making systemic conclusions about the 'New China'. Particularly if they're aware of unedifying local incidents like this one and Chen Yonglin's reception at Melbourne University last year, which occurred not merely outside China but within western universities, the institutional embodiment of free expression.

The last thing China needs is an image as a country of nationalist psychotics, who use past wrongs as an excuse to flout norms of civilised behaviour. Indeed the 'China Threat' lobby, which has long cast the Beijing regime as antisocial, has switched to painting the whole of Chinese society in these terms - a sort of high-tech Nazi Germany with a billion people. Still, it doesn't seem too much to expect respect from Chinese nationals for free speech, at least in other countries. It's not a hard concept - no one is obliged to tailor published material to others' sensitivities, short of hate speech or slander. And people express disagreement through reason, not insult and intimidation.

This should be doubly so in the case of academic enquiry. Stumbling across the MIT affair on China History Forum brought to mind an essay I wrote for a Japanese history subject a few years back on the 1894-5 war, including analysis of these same woodblock prints. Extracts follow -

This should be doubly so in the case of academic enquiry. Stumbling across the MIT affair on China History Forum brought to mind an essay I wrote for a Japanese history subject a few years back on the 1894-5 war, including analysis of these same woodblock prints. Extracts follow -

'... foreigners were looking at the war not as an ordinary (i.e. European) great power conflict, but as a contest between two Oriental peoples. Japan's achievement was seen in contrast with the staggering corruption and incompetence of the Chinese 'war effort', if it can be called such. Japanese professionalism was cast in glaring profile by the benighted state of the Chinese soldiery, which in the absence of proper training and armament relied on superstitions such as carrying lucky chickens into battle or eating ground tiger bone to induce courage. Mutilation of prisoners, pillage of the civilian population and medieval practices like offering rewards for Japanese heas completed the image of a confrontation between modern civilisation and barbarity

'[in] contemporary woodblock prints... with their western uniforms and equipage, dignified poise and orderly dispositions, the Japanese soldiers in these pictures personify modernity. By contrast the Chinese, with their anachronistic display of colours and polearms, appear in a continuous state of chaos and defeat. The prints illustrate the triumph of modern substance over antiquated display...'

My essay was for a Japanese history subject, so it's written from a Japanese perspective. I felt no need to qualify it by listing Japanese atrocities against the Chinese people, by explaining that the Qing armies' dismal performance was not typical of Chinese history, by acknowledging that Japan borrowed its writing system, architecture and form of government from China etc. Yet had this been on the MIT website, I might have received the same treatment as Professors Dower and Miyawaga. Indeed being Chinese, I could have expected additional epithets revolving around 'race traitor'.

Remembrance and justice are one thing, hatred is another. These outbursts don't help China's civil society, Japanese attitudes or East Asia's political environment, which seems to be getting more corrosive by the year. Sometimes it seems to students of the region that nothing has really changed since Japan smashed the old order a hundred-plus years ago, failing to put something constructive in its place. And where better to reflect on that momentous war than MIT's online exhibition, which remains up and running - with a few modifications.

Non sequitur

The scheme by Japan's foreign minister to rope foreign ambassadors into a World War II commemoration has fallen through, apparently after Taro Aso realised they weren't going to grace an official function led by a man who refuses to acknowledge that his daddy worked Allied POWs to death.

And Greg Sheridan, who nearly self-immolated over the AWB affair, has utterly redeemed himself in my eyes with this piece on that other fractious Asian relationship (Australia-Indonesia). Not one line in that article I disagree with.

And Greg Sheridan, who nearly self-immolated over the AWB affair, has utterly redeemed himself in my eyes with this piece on that other fractious Asian relationship (Australia-Indonesia). Not one line in that article I disagree with.

1 comment:

Re Sheridan on ALP foreign policy, only fair to hear both sides.

Post a Comment